Press Release

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎

The summer of 2019 marked a major transitional period for me and my art practice. I discovered Joshua Abelow’s work and his book Painter’s Journal (2012) about his early years living and making art in New York City. He is a graduate of RISD’s painting department, where I’m in school now. His book was recommended to me by a mentor. It gave voice to my insecurities involving love, location, and navigating my art practice within contemporary culture and the larger context of art history. That same summer was also when I met Abelow for the first time at the opening of a show he curated called Freddy’s World for Brooklyn-based gallery Fisher Parrish. His work is significant to me as a painting student in that, while he is very much a painter, his practice involves more than making paintings. He draws, writes, and curates shows of artists he admires. He ran an art blog called Art Blog Art Blog that predated the current surge of online art viewing spaces. The blog then morphed into a physical gallery called Freddy, which serves both as a highly conceptual curatorial project as well as Abelow’s alter ego. It’s like he gave a name and persona to his art practice, separate from himself, which is inline with the meta-nature of his ethos. And the way his work has been published in print, on the Internet, and shown in numerous galleries is a part of his effort to expand his (and our) literacy of the world. These ideas lay a foundation for the project I run, Apartment 13, in which I share work that I love with my schoolmates at RISD in Providence, RI, using my apartment. This solo presentation of Abelow’s work, Weird Science, is the project’s second installment.

There is a deeper, existential struggle in this show’s 20 paintings that makes me want to cling tightly to any feeling of hope I can manage to access in this new world of ours. As a society, we’ve settled into a shared, poignant malaise marked by a sudden reconciliation; shock quickly followed by acceptance quickly followed by defeat and then exhaustion. All I can hope for in the future is physical closeness again.

The day I set up the show with my girlfriend, Baijun, a friend returned from LA to Providence for a night and came over to check it out. It was wonderful, having not seen any friends since early March, to see this one. In a conversation we had, he brought up an article he read called, “Barnett Newman Made My Mom Cry,” in which an artist recalls the time he, as a child, went with his family to see Newman’s Sanctions of the Cross and his mother cried at the paintings, claiming they were “making fun of her Jesus.” Later in the article, the artist, now around the same age as his mom when the incident happened, decided to see the paintings after all the time that had passed. He stepped into the museum room, filled with the paintings that caused such grief to his mother’s faith long ago, and after a good look, in deep reverence,

he smiled.

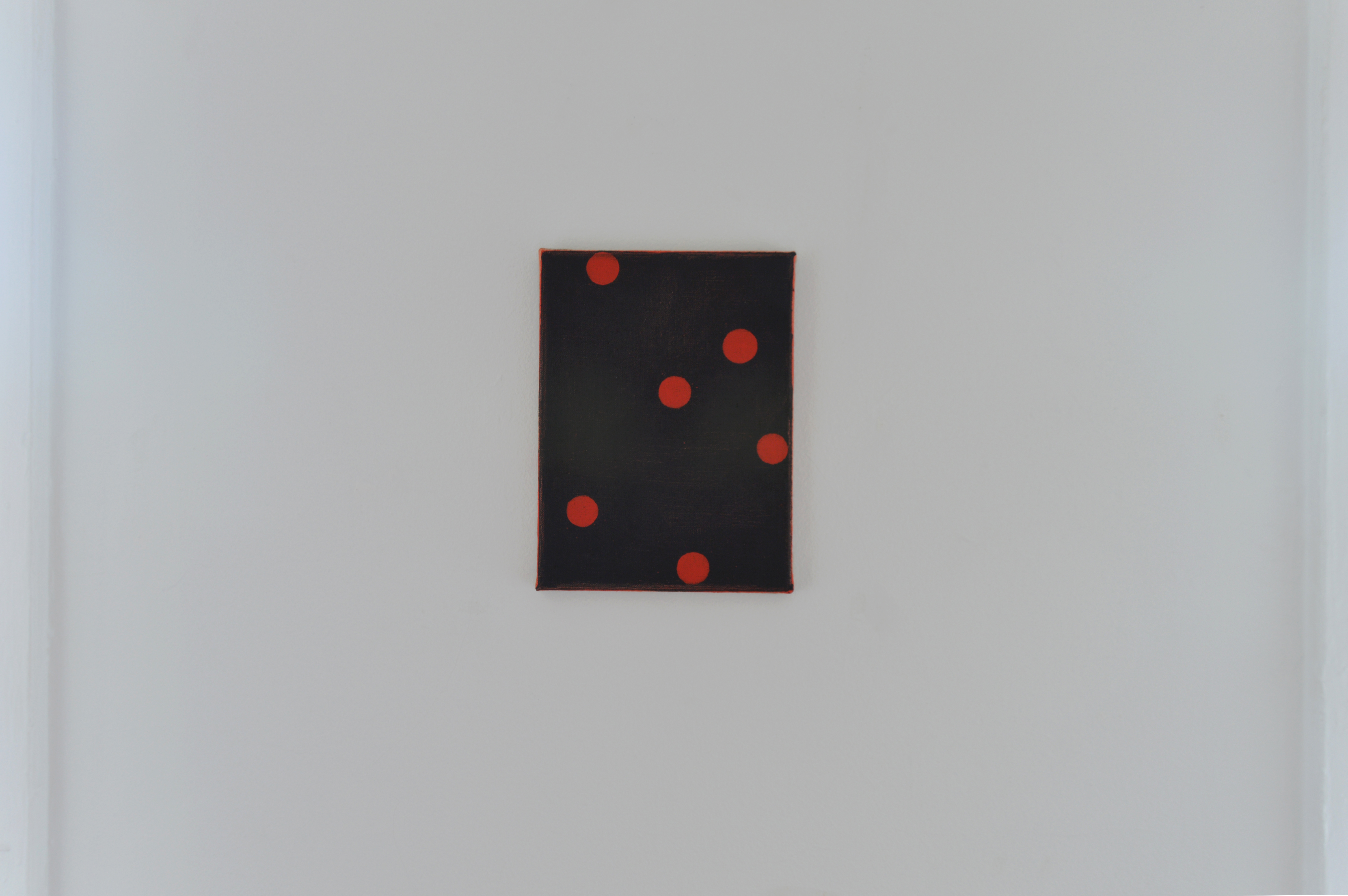

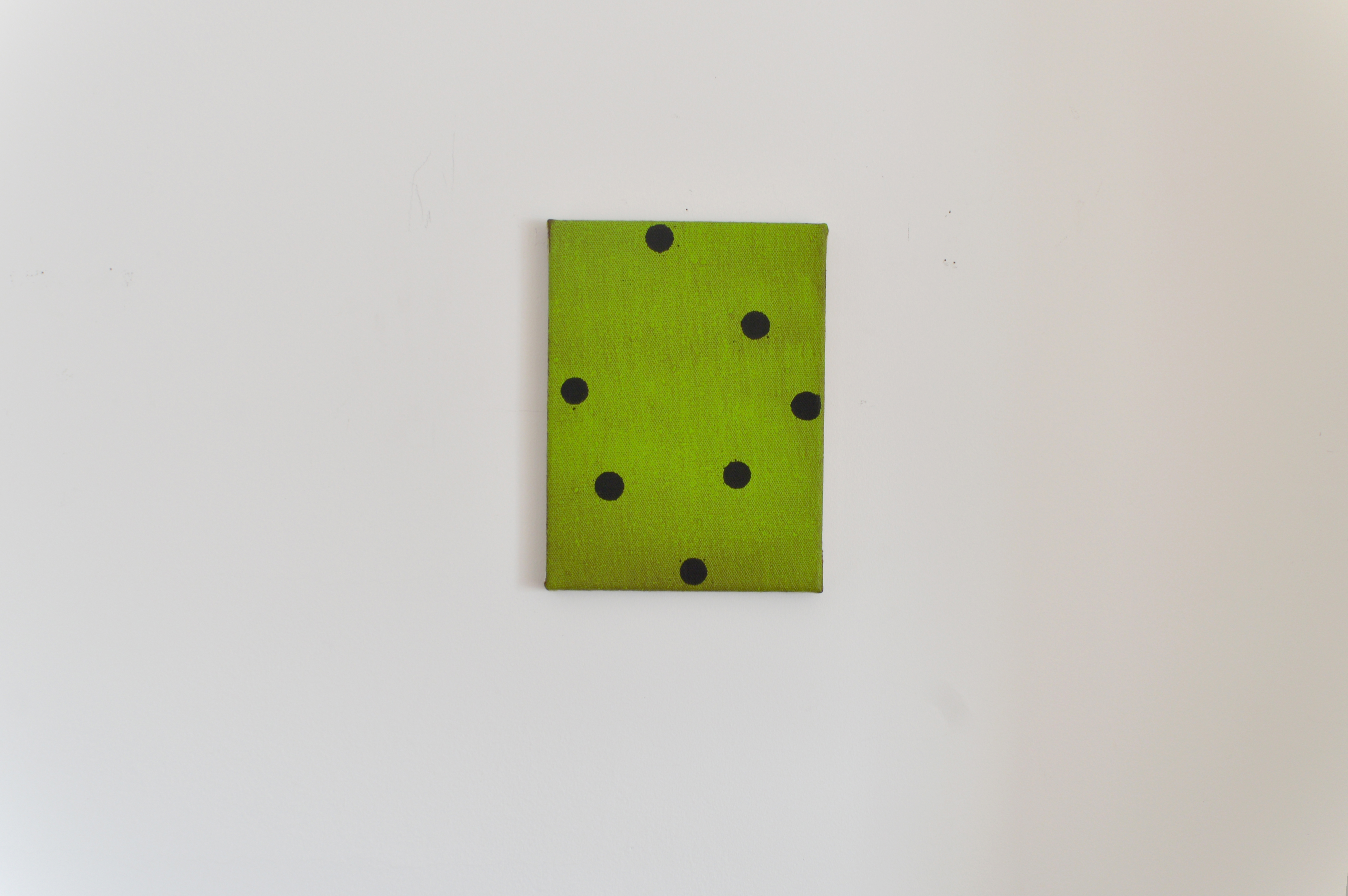

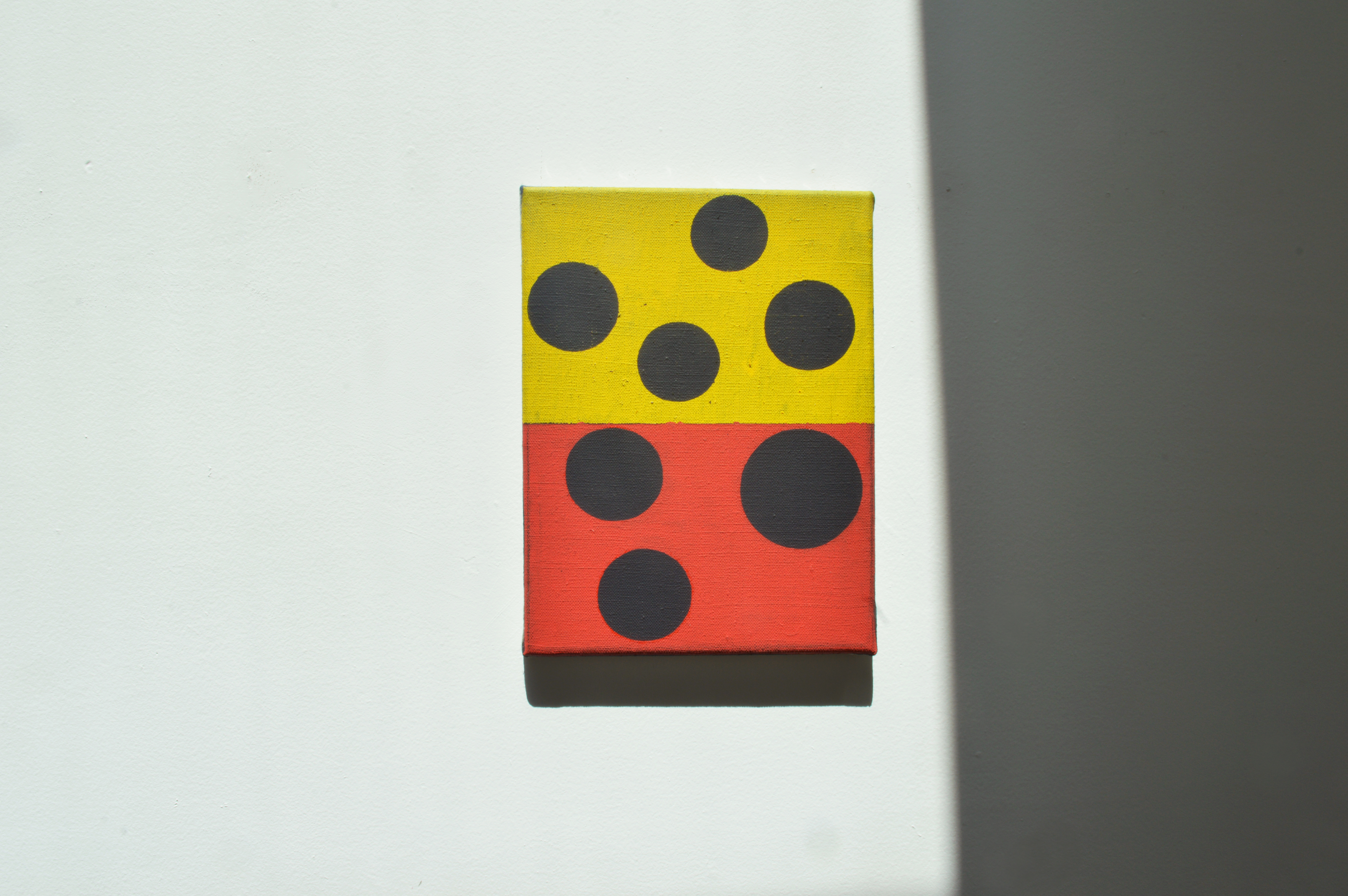

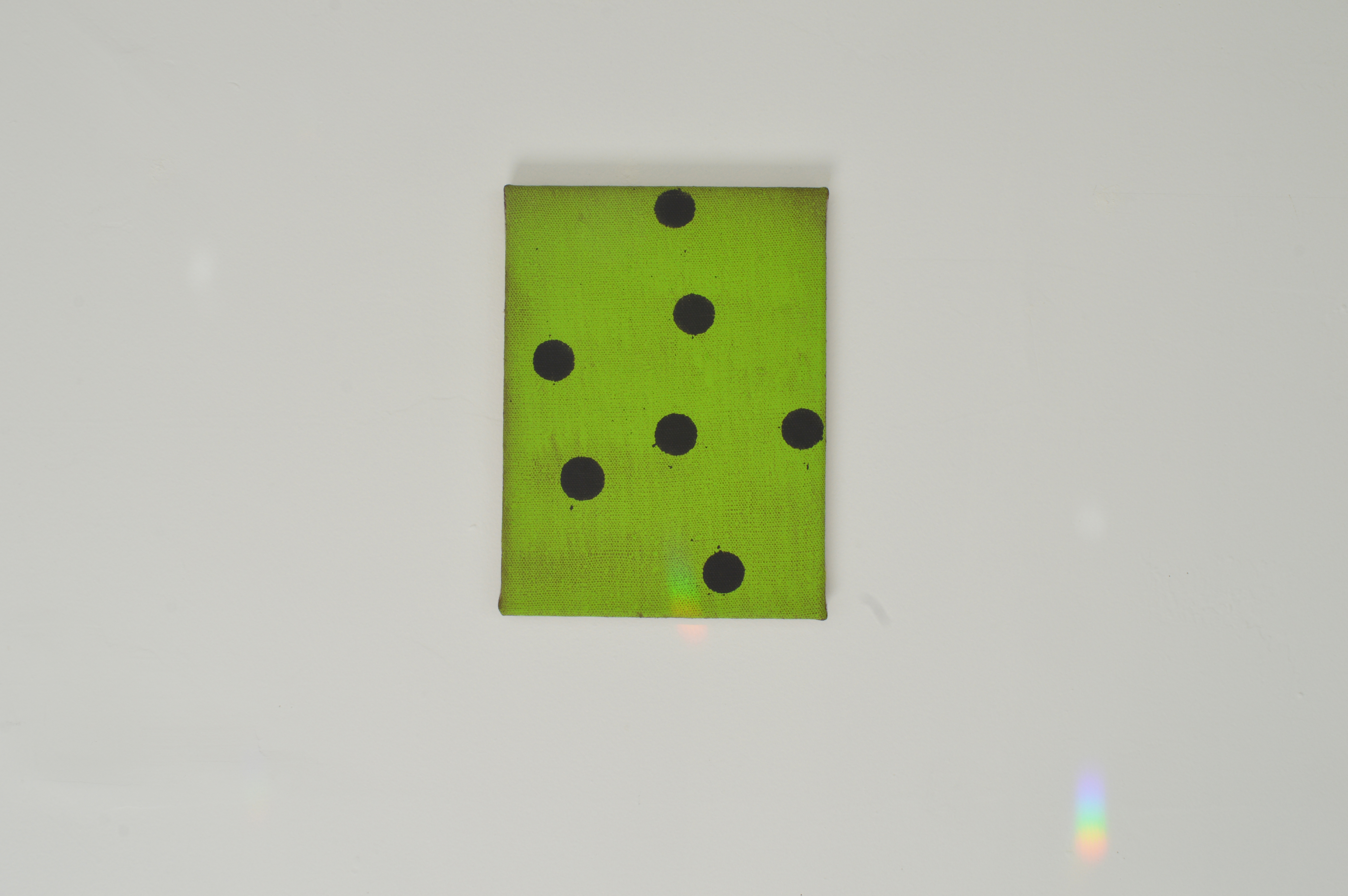

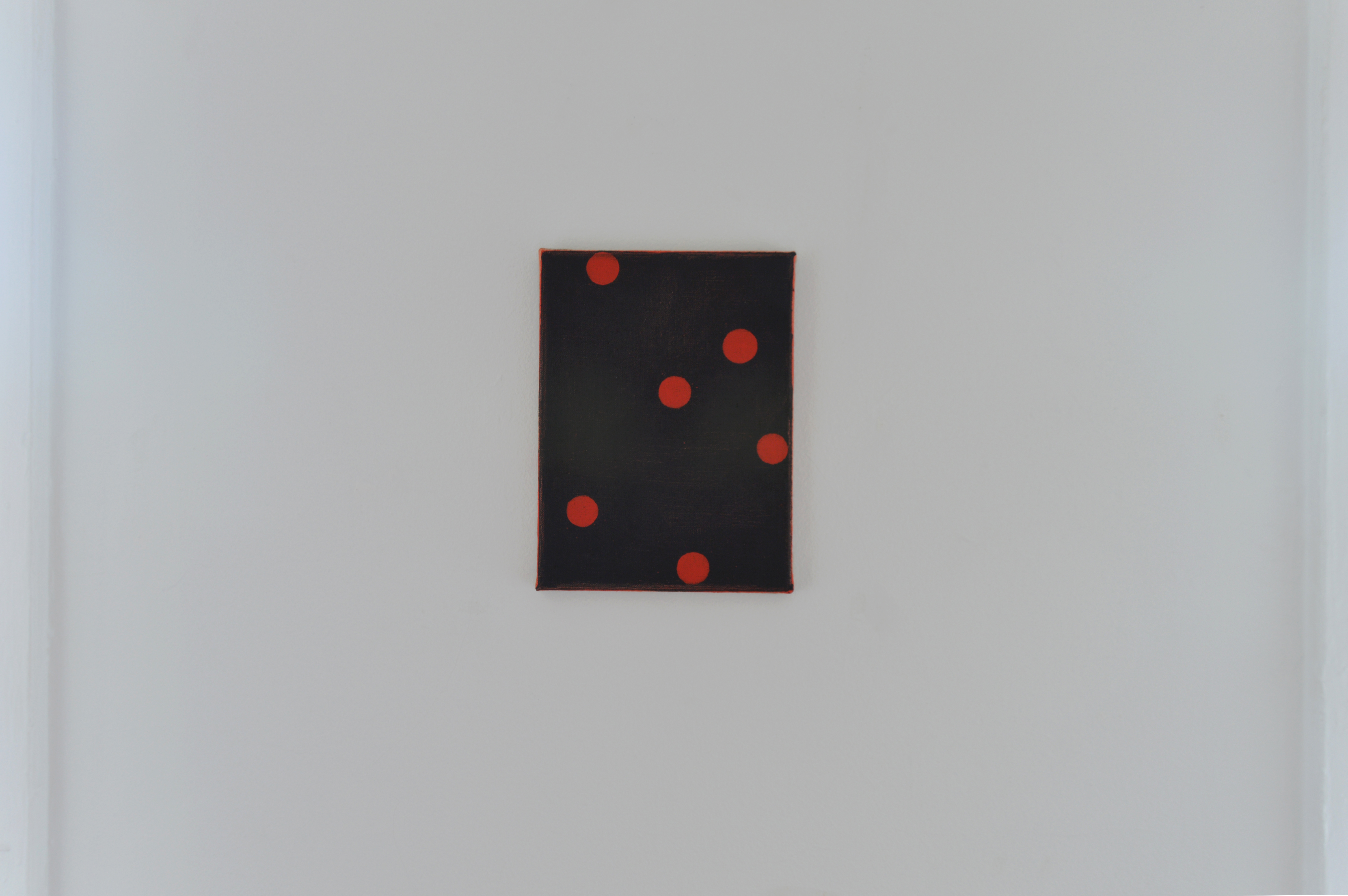

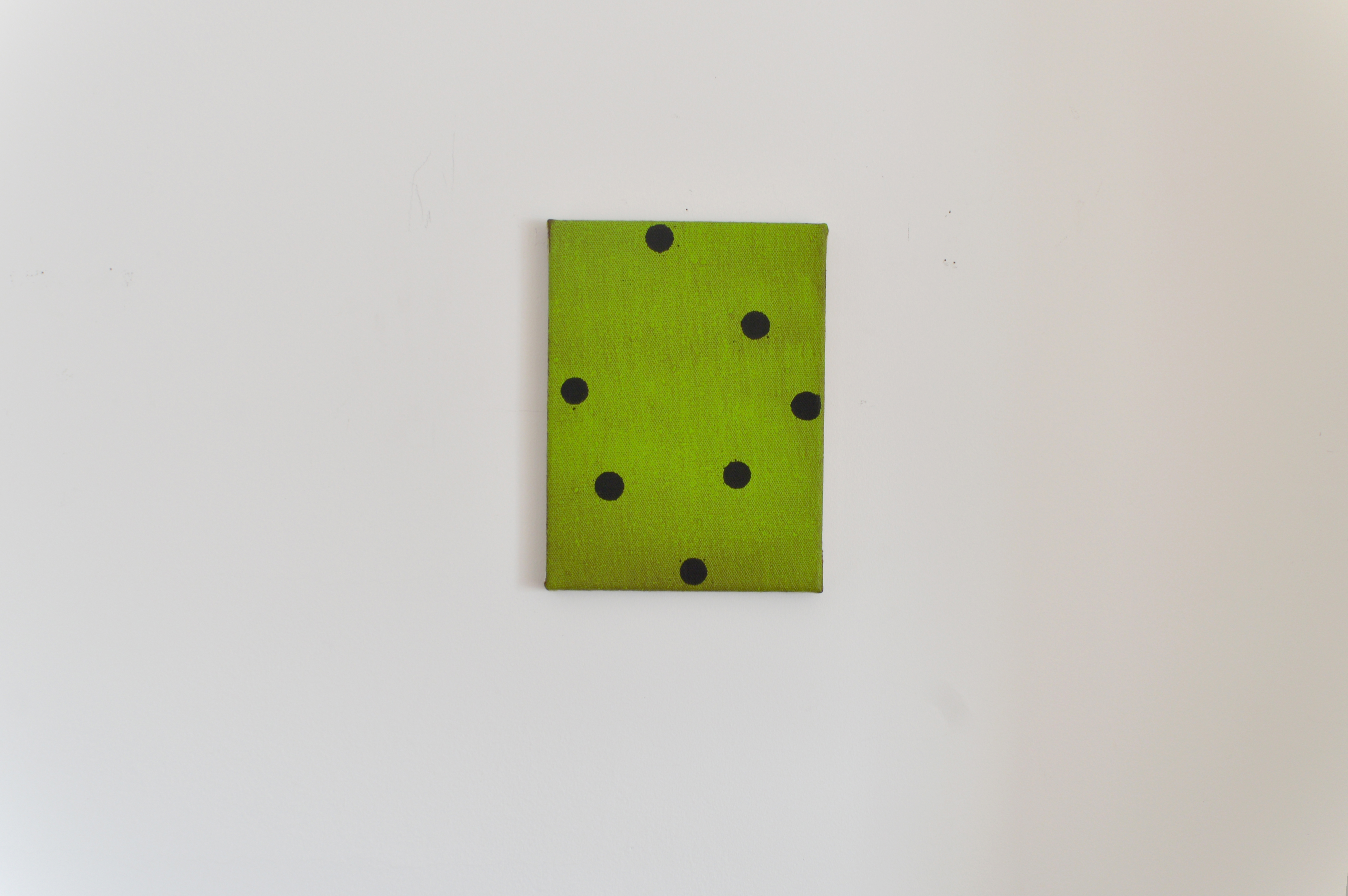

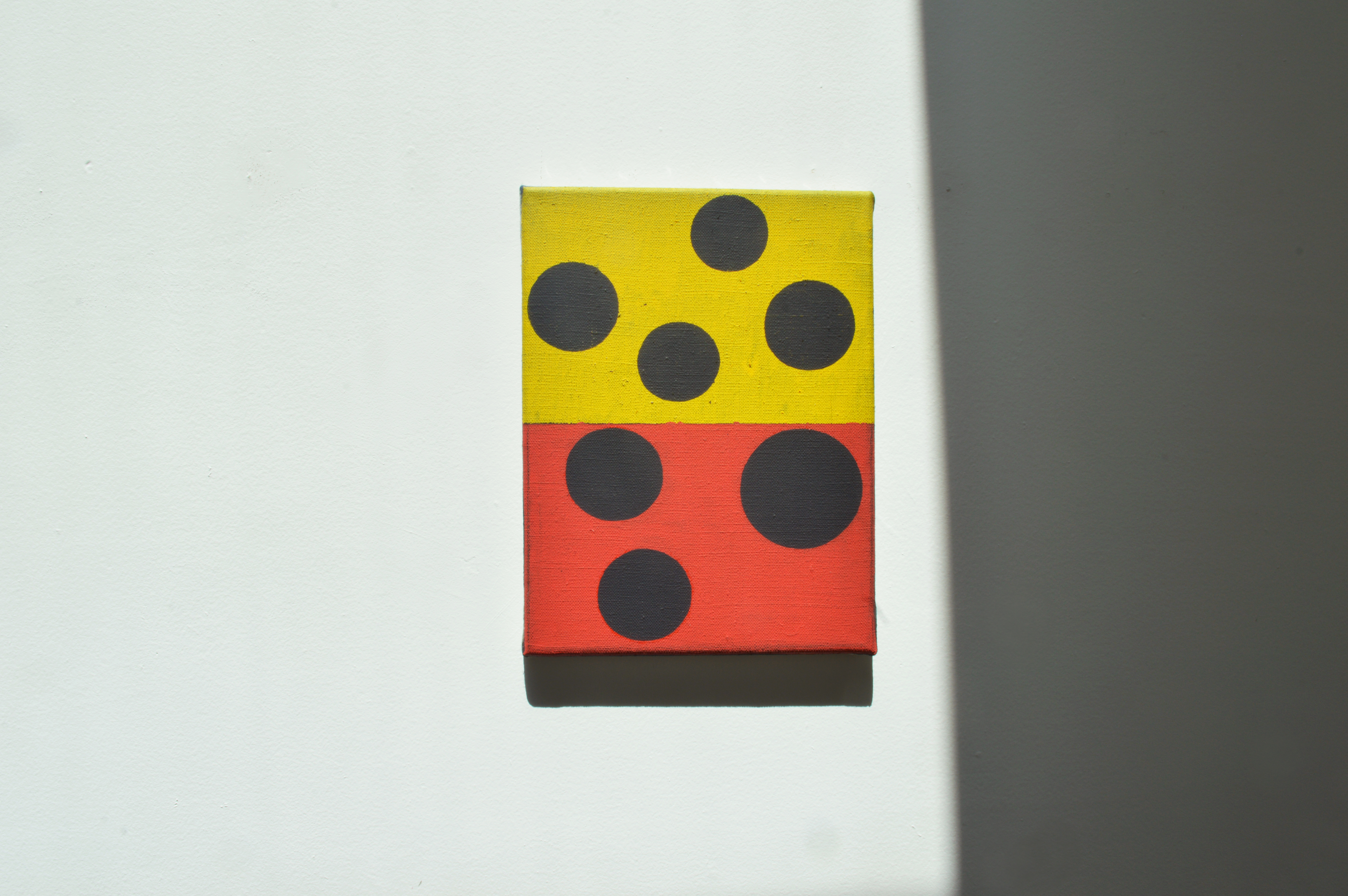

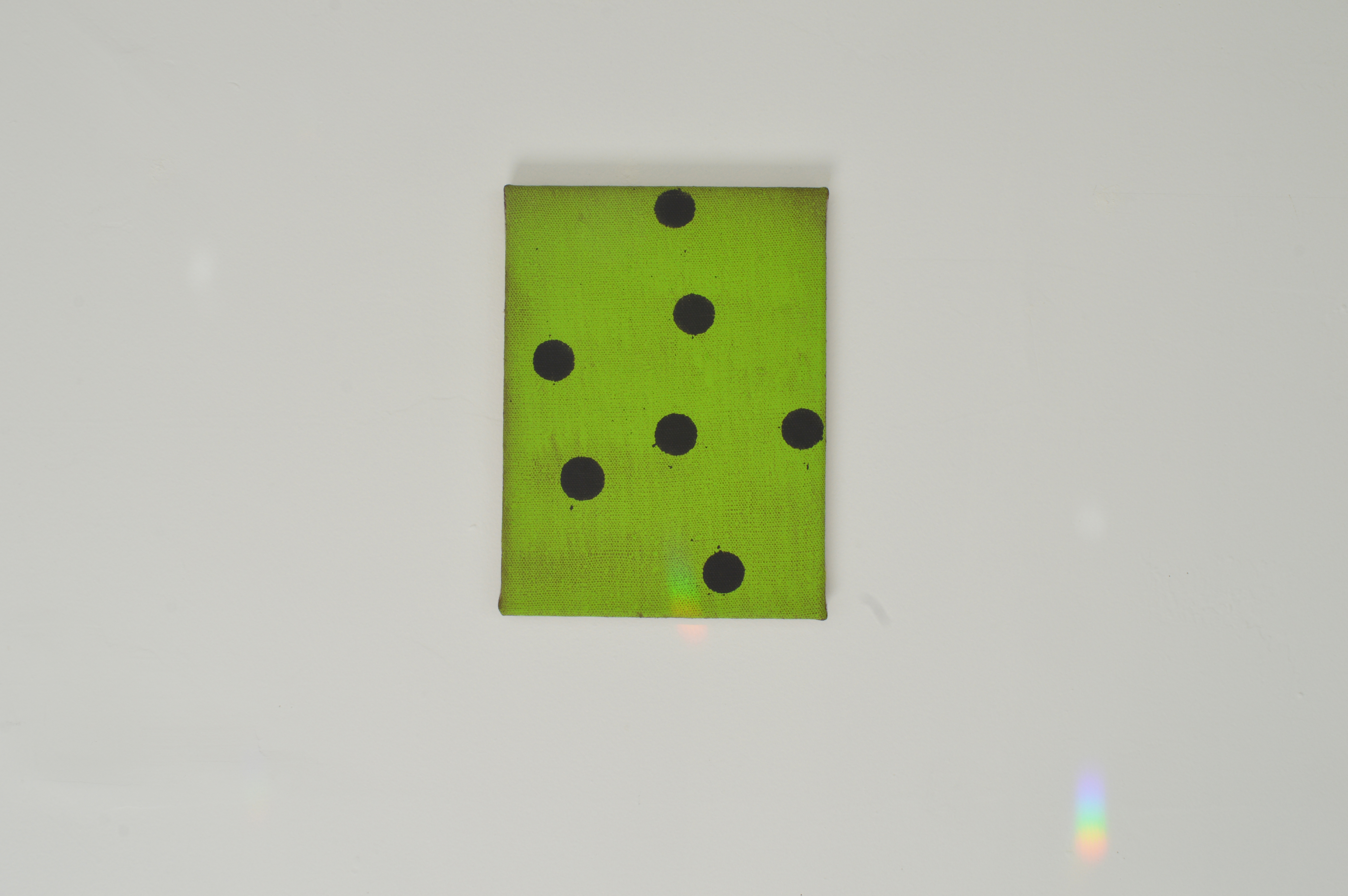

The very next day at 10 AM, Baijun and I started documenting the show. It’s hard to describe the disorienting feeling we had from waking up to this new setup. In place of our belongings and furniture were 20 abstract paintings hung on both floors of the complex. For a moment, everything felt desolate and somber. A melancholy but fitting testimony to the feelings we’ve had since our semester at RISD was cancelled in March. 16 of the 20 paintings (all 2017) have six to seven dots arranged on a horizontally split or flat plane with no real direction. In a way, these dots are helpless. Registering their vulnerability was cathartic for me. The four other paintings (all 2020) are in a familiar language and mythos of Abelow’s work--squares, diagonal lines, triangles—but with new graphic explosions fighting their way in. The bleeding taped off edges combined with crisp layered washes of color are a moody backdrop for the soft-edged explosions and their cold, dreary color. The color very passively dissipates these bursts with subdued intensity. This composition repeated in the four works seems like a silent plea rather than an exclamation. There is no immediately discernible prospect or destiny in the paintings, nor is there a trail to any possible answers; we are presented with truths that reflect our current monotonous reality: an indefinite pause on how we previously lived and felt about life.

The transition I was referring to in the summer of 2019 was related to me accepting myself and rejecting the idea that being young or without a strict trajectory meant that I couldn’t possibly fail. I couldn’t fail because I didn’t even know what would constitute a failure. The current feeling of aimlessness, with its lack of agency, that we all have right now reminds me of the chance that I might fail as an artist, even as a human. Maybe the failure I didn't know about at the time was my own lack of direction and ambition. As the dots in the paintings just drift, or bounce around on planes of mysterious color, without aim, I feel our collective vulnerability. It’s an emotional way of seeing the work, heightened by the fact that this space is our home.

Around 1 PM, on the second floor, rays of sun from the skylight passed through a small crystal ball my roommate hung on a ceiling pipe when we first moved in. Rainbow dots of light then populated the walls just like the dots in the paintings do. Some dots even landed on the canvases. After a good look, in deep reverence,

I smiled.

—Joshua K.Y. Boulos

05.05.2020

05.05.2020

Documentation by Baijun Chen and Joshua Boulos.

Huge thank you to Rachel Willis for editing the press release.

Joshua Abelow is an artist based in Harris, NY, who’s studio practice spans artmaking, writing, and curating. He is the founder of ART BLOG ART BLOG and runs Freddy, a curatorial space in an abandoned church in which he lives and works, in Harris, NY.

https://joshuaabelow.com/

https://freddygallery.biz/

Joshua Abelow 05/05/2020

Weird Science

Press Release

︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎︎The summer of 2019 marked a major transitional period for me and my art practice. I discovered Joshua Abelow’s work and his book Painter’s Journal (2012) about his early years living and making art in New York City. He is a graduate of RISD’s painting department, where I’m in school now. His book was recommended to me by a mentor. It gave voice to my insecurities involving love, location, and navigating my art practice within contemporary culture and the larger context of art history. That same summer was also when I met Abelow for the first time at the opening of a show he curated called Freddy’s World for Brooklyn-based gallery Fisher Parrish. His work is significant to me as a painting student in that, while he is very much a painter, his practice involves more than making paintings. He draws, writes, and curates shows of artists he admires. He ran an art blog called Art Blog Art Blog that predated the current surge of online art viewing spaces. The blog then morphed into a physical gallery called Freddy, which serves both as a highly conceptual curatorial project as well as Abelow’s alter ego. It’s like he gave a name and persona to his art practice, separate from himself, which is inline with the meta-nature of his ethos. And the way his work has been published in print, on the Internet, and shown in numerous galleries is a part of his effort to expand his (and our) literacy of the world. These ideas lay a foundation for the project I run, Apartment 13, in which I share work that I love with my schoolmates at RISD in Providence, RI, using my apartment. This solo presentation of Abelow’s work, Weird Science, is the project’s second installment.

There is a deeper, existential struggle in this show’s 20 paintings that makes me want to cling tightly to any feeling of hope I can manage to access in this new world of ours. As a society, we’ve settled into a shared, poignant malaise marked by a sudden reconciliation; shock quickly followed by acceptance quickly followed by defeat and then exhaustion. All I can hope for in the future is physical closeness again.

The day I set up the show with my girlfriend, Baijun, a friend returned from LA to Providence for a night and came over to check it out. It was wonderful, having not seen any friends since early March, to see this one. In a conversation we had, he brought up an article he read called, “Barnett Newman Made My Mom Cry,” in which an artist recalls the time he, as a child, went with his family to see Newman’s Sanctions of the Cross and his mother cried at the paintings, claiming they were “making fun of her Jesus.” Later in the article, the artist, now around the same age as his mom when the incident happened, decided to see the paintings after all the time that had passed. He stepped into the museum room, filled with the paintings that caused such grief to his mother’s faith long ago, and after a good look, in deep reverence,

he smiled.

The very next day at 10 AM, Baijun and I started documenting the show. It’s hard to describe the disorienting feeling we had from waking up to this new setup. In place of our belongings and furniture were 20 abstract paintings hung on both floors of the complex. For a moment, everything felt desolate and somber. A melancholy but fitting testimony to the feelings we’ve had since our semester at RISD was cancelled in March. 16 of the 20 paintings (all 2017) have six to seven dots arranged on a horizontally split or flat plane with no real direction. In a way, these dots are helpless. Registering their vulnerability was cathartic for me. The four other paintings (all 2020) are in a familiar language and mythos of Abelow’s work--squares, diagonal lines, triangles—but with new graphic explosions fighting their way in. The bleeding taped off edges combined with crisp layered washes of color are a moody backdrop for the soft-edged explosions and their cold, dreary color. The color very passively dissipates these bursts with subdued intensity. This composition repeated in the four works seems like a silent plea rather than an exclamation. There is no immediately discernible prospect or destiny in the paintings, nor is there a trail to any possible answers; we are presented with truths that reflect our current monotonous reality: an indefinite pause on how we previously lived and felt about life.

The transition I was referring to in the summer of 2019 was related to me accepting myself and rejecting the idea that being young or without a strict trajectory meant that I couldn’t possibly fail. I couldn’t fail because I didn’t even know what would constitute a failure. The current feeling of aimlessness, with its lack of agency, that we all have right now reminds me of the chance that I might fail as an artist, even as a human. Maybe the failure I didn't know about at the time was my own lack of direction and ambition. As the dots in the paintings just drift, or bounce around on planes of mysterious color, without aim, I feel our collective vulnerability. It’s an emotional way of seeing the work, heightened by the fact that this space is our home.

Around 1 PM, on the second floor, rays of sun from the skylight passed through a small crystal ball my roommate hung on a ceiling pipe when we first moved in. Rainbow dots of light then populated the walls just like the dots in the paintings do. Some dots even landed on the canvases. After a good look, in deep reverence,

I smiled.

There is a deeper, existential struggle in this show’s 20 paintings that makes me want to cling tightly to any feeling of hope I can manage to access in this new world of ours. As a society, we’ve settled into a shared, poignant malaise marked by a sudden reconciliation; shock quickly followed by acceptance quickly followed by defeat and then exhaustion. All I can hope for in the future is physical closeness again.

The day I set up the show with my girlfriend, Baijun, a friend returned from LA to Providence for a night and came over to check it out. It was wonderful, having not seen any friends since early March, to see this one. In a conversation we had, he brought up an article he read called, “Barnett Newman Made My Mom Cry,” in which an artist recalls the time he, as a child, went with his family to see Newman’s Sanctions of the Cross and his mother cried at the paintings, claiming they were “making fun of her Jesus.” Later in the article, the artist, now around the same age as his mom when the incident happened, decided to see the paintings after all the time that had passed. He stepped into the museum room, filled with the paintings that caused such grief to his mother’s faith long ago, and after a good look, in deep reverence,

he smiled.

The very next day at 10 AM, Baijun and I started documenting the show. It’s hard to describe the disorienting feeling we had from waking up to this new setup. In place of our belongings and furniture were 20 abstract paintings hung on both floors of the complex. For a moment, everything felt desolate and somber. A melancholy but fitting testimony to the feelings we’ve had since our semester at RISD was cancelled in March. 16 of the 20 paintings (all 2017) have six to seven dots arranged on a horizontally split or flat plane with no real direction. In a way, these dots are helpless. Registering their vulnerability was cathartic for me. The four other paintings (all 2020) are in a familiar language and mythos of Abelow’s work--squares, diagonal lines, triangles—but with new graphic explosions fighting their way in. The bleeding taped off edges combined with crisp layered washes of color are a moody backdrop for the soft-edged explosions and their cold, dreary color. The color very passively dissipates these bursts with subdued intensity. This composition repeated in the four works seems like a silent plea rather than an exclamation. There is no immediately discernible prospect or destiny in the paintings, nor is there a trail to any possible answers; we are presented with truths that reflect our current monotonous reality: an indefinite pause on how we previously lived and felt about life.

The transition I was referring to in the summer of 2019 was related to me accepting myself and rejecting the idea that being young or without a strict trajectory meant that I couldn’t possibly fail. I couldn’t fail because I didn’t even know what would constitute a failure. The current feeling of aimlessness, with its lack of agency, that we all have right now reminds me of the chance that I might fail as an artist, even as a human. Maybe the failure I didn't know about at the time was my own lack of direction and ambition. As the dots in the paintings just drift, or bounce around on planes of mysterious color, without aim, I feel our collective vulnerability. It’s an emotional way of seeing the work, heightened by the fact that this space is our home.

Around 1 PM, on the second floor, rays of sun from the skylight passed through a small crystal ball my roommate hung on a ceiling pipe when we first moved in. Rainbow dots of light then populated the walls just like the dots in the paintings do. Some dots even landed on the canvases. After a good look, in deep reverence,

I smiled.

—Joshua K.Y. Boulos

05.05.2020

05.05.2020

Documentation by Baijun Chen and Joshua Boulos.

Huge thank you to Rachel Willis for editing the press release.

Joshua Abelow is an artist based in Harris, NY, who’s studio practice spans artmaking, writing, and curating. He is the founder of ART BLOG ART BLOG and runs Freddy, a curatorial space in an abandoned church in which he lives and works, in Harris, NY.

https://joshuaabelow.com/

https://freddygallery.biz/

Huge thank you to Rachel Willis for editing the press release.

Joshua Abelow is an artist based in Harris, NY, who’s studio practice spans artmaking, writing, and curating. He is the founder of ART BLOG ART BLOG and runs Freddy, a curatorial space in an abandoned church in which he lives and works, in Harris, NY.

https://joshuaabelow.com/

https://freddygallery.biz/